How Dutch submarine Walrus ‘torpedoed’ a US aircraft carrier

In 1999 HNLMS Walrus ‘torpedoed’ the Nimitz class aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, plus seven escort ships, during an exercise in the Atlantic. Jan Hubert Hulsker, then commanding officer of HNLMS Walrus, talks about that successful exercise for the first time.

HMNLS Walrus in 2017. Walrus is the first boat of the Walrus class, which consists of four diesel electric submarines. These boats were built in Rotterdam and put into service in the early 1990s. They will be replaced around 2034. (Photo: Dutch MOD)

This article was first published on Marineschepen.nl in 2016 and has now been updated and translated for an international audience.

One can find online stories about Swedish and French submarine successes during exercises against aircraft carriers. The story about the Walrus is lesser known.

The book In Deepest Secrecy; Dutch submarine espionage operations from 1968 to 1991 describes sixteen submarine operations, based on secret information about these patrols (that more or less accidentally ended up in the Dutch National Archives).

A part of the story on the successful exercise had been published on the website Dutchsubmarines.com earlier, but even after 17 years, the story had not been told in full. So to find out more, Jaime Karremann (editor-in-chief of Dutch naval website Marineschepen.nl) interviewed the man who looked through the periscope, received all the information, and made the decision to attack in 1999: the then 35-year-old Lieutenant Commander (LTZ1) Jan Hubert Hulsker.

In addition to the interview, the author has used the logbook of HNLMS Walrus for this article.

USS Theodore Roosevelt, commissioned in 1986, is one of the ten Nimitz class carriers. Picture taken in 2018. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Alex Corona)

Largest concentration of power since 1990

Back in February 1999, LTZ1 Jan Huber Hulsker had been commander of the submarine HNLMS Walrus for a year and a half. This submarine, designed and built in the Netherlands, participated in the Joint Task Force Exercise/ Theater Ballistic Missile Defense Initiative 1999 (JTFEX/ TMDI99), known as JTFEX 99-1 for short.

A Belgian-Dutch taskforce also participated, consisting of frigate HNLMS De Ruyter, oiler HNLMS Zuiderkruis, frigate HNLMS Van Nes, and the Belgian frigate BNS Wandelaar, plus two Royal Netherlands Navy P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft.

JTFEX 99-1, involving 24,000 men and women, 15,000 of them at sea, was the largest concentration of power since the 1990 Gulf War. The training area stretched from Norfolk, Virginia, to Puerto Rico.

The main event was the amphibious landing of 2,100 marines from the Amphibious Ready Group consisting of the USS Kearsage, USS Ponce, and USS Gunston Hall, protected by warships from the U.S., France and the BE-NL taskforce.

The Carrier Battle Group led by the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt, including F-14 Tomcats, was responsible for air defense and attacks on land, and enjoyed the protection of U.S., Canadian and German naval vessels.

Jan Hubert (Huub) Hulsker sailed on various Dutch submarines from 1985 to 2001, and was commander of HNLMS Walrus and later HNLMS. Bruinvis. After various jobs on shore, including at NATO, Hulsker took command of the oiler HNLMS Amsterdam and then LPD HNLMS Rotterdam. Hulsker left the Royal Netherlands Navy in 2022, when he was Deputy Commander in the rank of Rear Admiral. (Photo: John van Helvert/ Dutch MOD)

Bad guys

All units gathered in the naval port of Norfolk on the east coast of the U.S. at the end of February. “We had a very nice reception on an American submarine,” Hulsker recalls. “But we hadn’t been given any information about the exercise at that point. I thought that was a bit strange, because if you do such a large exercise in Europe, you get a thick book of instructions and information.”

“On the day of departure, we were provided with a few sheets of information. That was it – no briefing or presentation. But everything I wanted to know was on there: it was just a free exercise. We were in a large area, we were the bad guys and the carrier was the good guy.”

“The man who handed me the package – I will never forget it – added: ‘You are going to lose. Don’t be disappointed, but now you already know. Because of course the carrier has to win.'”

A bit surprised, Hulsker took the papers, but was glad that there were no detailed instructions.

Searching for the enemy in a large pool of water

The exercise began and the Walrus headed out to sea in search of prey.

The Walrus operated alone, but Hulsker did hear after a while that many of his allies were being eliminated. The ‘good guys’ formed a formidable opponent. The Nimitz class carriers are unmatched by any surface vessel in the world.

The loss of a carrier plus thousands of crew members could mean the end of a war, because if one is sunk, seemingly no ship is safe.

These carriers are therefore surrounded by ships, submarines, and aircraft for defense.

A Carrier Battle Group boasts a tremendous amount of power. But it is the submarine (including the relatively cheap and small diesel-electric ones) that can be a nightmare for a carrier.

However, not everyone was convinced. Confident of victory, the Carrier Battle Group sailed through the waters of the Atlantic in February 1999 with the USS Theodore Roosevelt as its main body.

The consequences of a successful attack with a heavyweight torpedo like the Mk 48 are disastrous, because it does not hit its target but explodes under the ship. Ships the size of a frigate will break into two and sink in a few minutes. Moreover, a torpedo can attack again after a miss, and to date no working defense against a torpedo is operational. How many torpedoes are needed to sink a Roosevelt-sized aircraft carrier is not publicly known. Public, but unconfirmed, sources speak of 1 to 6 Mk 48 torpedoes. (Photo: Royal Australian Navy)

Silence

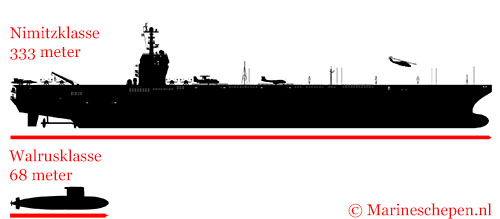

In that same Atlantic Ocean, HNLMS Walrus was hidden in an almost endless sea. Sailing slowly, at a speed of a few knots, the 68-meter-long submarine remained close to the surface.

Hulsker repeatedly raised the periscope to scan the horizon, hoping to see a mast. He knew there was a chance he wouldn’t discover anything at all, because the periscope’s range is limited. The lenses and prisms are of the highest quality, but the periscope sticks out just above the waves. A ship only 30 km away can therefore pass unseen and that chance is very high in a designated sea area of hundreds of square kilometers.

That is why the sonar is a submarine’s most important sensor. In the control room, the sonar operators listened to propeller noise and ship engines. A submarine can use its passive sonar to detect surface vessels at a very great distance, but the sonar conditions during the exercise prevented this.

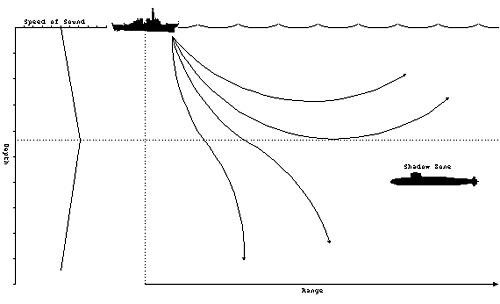

Temperature layers and salinity have a major influence on how sound propagates underwater. Temperature layers always vary due to, for example, currents and the time of year. Hulsker had those layers measured regularly, so on board the Walrus people knew exactly what the situation was.

Sound waves are strongly influenced underwater. Here is an example of the effect of a temperature layer on the sound waves of an active sonar. The submarine therefore remains undetected. (Source: Introduction to Naval Weapons Engineering course syllabus, 1998, U.S. Navy)

“The range of our passive sonars was very limited due to temperature layers,” says Hulsker. But the ranges of the sonars of the surface ships were also minimal.

Partly for this reason, the surface ships did not use their active sonar (which emits a loud ping that must bounce off an object). A disadvantage of the active sonar is that submarines hear the ‘ping’ at enormous distances. By keeping quiet, the Carrier Battle Group hoped to slip through the submarine net undetected.

Almost all American ships, as well as the Canadian frigate, also had passive sonar in the form of an almost 2 km-long cable with hydrophones. With this towed array it is possible to listen under temperature layers. It is not known whether they used them, but they probably did. The ships were therefore not completely deaf.

However, Hulsker had another trump card: Electronic Warfare (EW). That turned out to be vital, because the ships constantly searched the airspace with their radars, so the Walrus received the transmitted signals with the raised EW mast, without the onrushing opponents knowing.

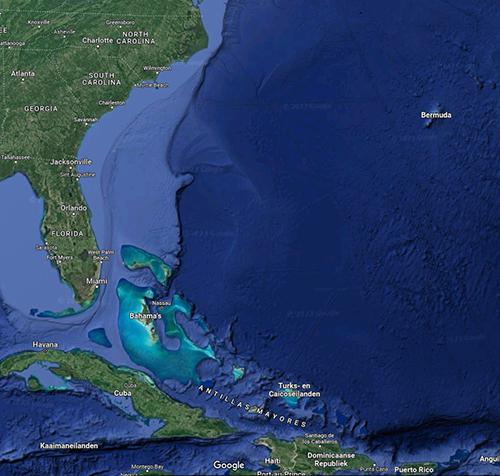

The exercise area. In addition to the layers, the seabed also plays a role. On the U.S. East Coast, this is a disadvantage for surface vessels with active sonar. The seabed is at a depth of about 100 meters on the continental shelf and suddenly drops to 3 kilometers. The Gulf Stream that passes by also causes a lot of noise and false contacts. (Source: Google Maps)

Carrier!

Hulsker and his team did not have to wait very long for contact. One day after departure, the Walrus torpedoed an Arleigh Burke class destroyer. The following day, according to the ship’s log, the submarine even launched torpedoes at three of these types of destroyers.

It didn’t stop there. The next day, the EW operator suddenly detected multiple radars from one direction. “So there must be something interesting there and I decided to go for it,” says the then commander. HNLMS Walrus went deep and headed in the direction of the source of the electromagnetic signals.

After several hours Hulsker gave the order to return to periscope depth and the thin attack periscope was raised.

“I looked through the periscope and immediately saw masts of an aircraft carrier. You have to be careful, because when you look for a carrier everything looks like a carrier. But this time it could not be anything else, so I decided – and that is a classic maneuver, because you also learn that during submarine command training – to go deep and do an interception on the carrier.”

After estimating the aircraft carrier’s course and speed, Walrus’ team quickly calculated where the submarine should intercept the carrier. The sub picked up speed and slid into the depths. It headed as quietly as possible toward the group of ships.

At the predetermined time, Hulsker ordered it to rise again to periscope depth, about 60 feet (19 m) below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. “As we approached periscope depth, we also got contacts on the sonar. The screens filled with information, but the adversary still hadn’t figured it out. They had their active sonar off and their passive sonars couldn’t hear us as the Walrus class is extremely quiet.”

Back at periscope depth, Hulsker decided to raise the periscope again. That is not without risks, because there is always a chance that the periscope will be seen by a lookout, an aircraft or a radar. But Hulsker was willing to take that risk: “It was an exercise, so I thought: ‘I’m going to take a good look at that carrier too.'”

The periscope slid up, and Hulsker quickly flipped down the levers and watched. What he saw was even better than he had expected: “I saw the escorts of the Roosevelt in the distance to our port and starboard sides, while the carrier was right in front of me, at a distance of 4,000 yards, heading toward me. I thought: ‘This is my day!'”

Hulsker was not afraid of the ships that the Walrus had passed, because “on frigates they mainly look forward.” So he took another good look at the Theodore Roosevelt: “I saw the F-14s taking off in front of me. You just don’t get a better picture than that,” Hulsker vividly remembers.

That image must be recorded, decided Hulsker, and ordered the navigation officer to take pictures of the Roosevelt through the periscope. “At that time we still had analog cameras on board and the navigation officer, a Canadian officer, took a series of photos.”

That was enough. It was time for the Walrus to attack. The control room and torpedo room were ready. “Shoot!” said Hulsker and water shot out of the empty torpedo tubes – a simulated shot. Hulsker then ordered a green smoke grenade to be fired – the signal during an exercise for a successful submarine attack.

The Walrus braced itself for the counter-attack.

But it remained silent.

“Apparently no one had seen that green grenade.”

Hulsker didn’t hesitate for a moment: “In a real war situation I would never do it, but I decided to go even closer.”

Quietly Walrus crept closer. “At about 1,500 yards we fired another green grenade.”

This time no one missed it: “All hell broke loose. Suddenly all the sonars in the northern hemisphere turned on – that’s how it felt – and helicopters took off. Everything that could ping turned on its sonar. It was a big panic, because having a green grenade fired 1500 yards from the carrier was really not part of their plan.”

The Walrus fits almost 40 times into a Nimitz class aircraft carrier. A submarine is therefore also called an asymmetric weapon. (Image: Jaime Karremann/ Marineschepen.nl)

Underneath

On the surface there was complete chaos, but Hulsker was not done with his prey. Instead of sailing away, he decided to head straight for the gigantic nuclear carrier with four almost 8-metre-large propellers, and sail underneath it: “For each ship, there is a calculation of how deep you have to go if you’re sailing underneath it. That was 30 meters for the Nimitz class. But then I looked at the Roosevelt again, and I thought: ‘You know what? I’m going a little deeper, because it’s really big.'”

“Then we literally passed underneath an 88,000-ton aircraft carrier. Our boat started to shake. There were crew members who jumped out of their beds and came to the control room to see what was going on.”

Once underneath the carrier, the search by the escort ships really got underway. That only provided more targets for the Walrus: “Anyone who turned on their sonar got a torpedo fired at them.” According to the ship’s log, three more frigates received a (simulated) torpedo within half an hour.

At the same time, the Walrus tried to escape: “There was so much noise at the time. We took advantage of that to get away.”

Halifax class frigate HMCS Ville de Quebec was one of Roosevelt’s escort ships. (Picture: Royal Canadian Navy)

Escaped?

According to Dutchsubmarines.com, HNLMS Walrus sneaked away undetected. But Hulsker is not sure: “There were attacks on us, but it is impossible to say whether they were successful.”

Surface ships reported that they simulated an attack by throwing a submarine grenade. However, that does not mean that the ship knew the correct position of the submarine and whether the torpedo had been fired in the right direction.

“I find it very difficult to say whether we escaped,” Hulsker looks back. “We snuck away after the attack, but this was never going to be entirely realistic. Because if that carrier really had sunk, there would haven been an incredible amount of noise in the water, making it even harder to detect and attack a submarine. Moreover, if I had really torpedoed the carrier, I would not have tried to sail underneath it. I didn’t even get that close before firing torpedoes. But after such an attack I don’t think the chances of survival are big. On the other hand, the escorts weren’t really on top of us.”

Submarine sunk or not, the good guys had lost a large number of vessels, including a carrier.

Also FGS Schleswig Holstein, a German Navy Brandenburg class frigate, was ‘torpedoed’ as well. (Picture: German Navy)

Morale boost

It didn’t matter to the crew whether the Walrus had escaped or not. Hulsker: “Everyone was thrilled to bits. You could sense it throughout the boat. The crew was extremely proud; they loved it!”

On the surface, however, not everyone was so happy. After the counter-attack by the Carrier Battle Group, the exercise became completely silent. Hulsker: “I received no messages, nothing at all. Nobody said anything. I had reported the attacks according to my orders. It wasn’t until the end of the exercise that I received a message from an admiral. He thanked us very much for the impressive attack. But that was it; it was hushed up.”

On board the submarine it was not. “We had a ship’s newspaper and the headline was ‘Theodore Roosevelt Torpedoed’. That was really funny. And the skipper drew a picture of a Walrus with a carrier in his mouth. It was painted on the sail.”

After the exercise, the Walrus headed for Charleston. “There the U.S. Navy had a nuclear submarine school and they had already heard the news. ‘Oh, that was you,’ they said.”

It was a nice port visit for the crew of the Walrus.

Not everything had gone perfectly, as it turned out later. During the torpedo attack the Canadian navigation officer who was ordered to take pictures of the USS Theodore Roosevelt had had no roll of film in his camera. Hulsker: “People got really angry. That Canadian guy was cursed by the whole boat.”

USS Theodore Roosevelt between the teeth of a walrus, painted on the sail of the submarine after the exercise. (Photo: private collection J.H. Hulsker)

Eight ships torpedoed

According to the ship’s logbook, Hulsker did all the attacks, but he cannot remember all the ships individually. The former commanding officer does confirm there were quite a number.

The ship’s log also confirms this. Below are the ships at which torpedoes were launched, according to the ship’s log:

• USS Theodore Roosevelt [aircraft carrier]

• 4 x Arleigh Burke class destroyer

• HMCS Ville de Quebec [frigate, Halifax class, Canada]

• OH Perry class frigate

• FGS Schleswig-Holstein [frigate, Brandenburg class, Germany]

Before 2005, the now inactive website Dutchsubmarines.com published some information about this exercise as well. According to that website, the Walrus sank no less than nine enemy ships. Whether that is true, however, is not certain, as the website does not mention the source of that information.

Instead of four destroyers, Dutchsubmarines.com says it was two destroyers, one Ticonderoga class, and the amphibious command ship USS Mount Whitney. Additionally, a torpedo attack on the Los Angeles class submarine USS Boise was mentioned.

Attacks on Mount Whitney and submarine Boise are not mentioned in the ship’s log, but Close Quarter Drill Submarine is mentioned several times.

Four times Walrus’ target was an Arleigh Burke class destroyer. USS Hopper was one of Roosevelt’s escorts at the time. Hopper is pictured here in 2018, arriving in the the 7th Fleet area of operations. (Picture: U.S. Navy)

Realistic?

It is interesting that the majority of the attacked ships were still fairly new in 1999. In addition, almost every ship had a passive towed array sonar, which was an important tool in anti-submarine warfare at the time.

Were operational restrictions imposed on the Theodore Roosevelt Strike Group? That doesn’t seem to have been the case. These exercises are meant for the units to learn and to improve. A U.S. Navy news report right before the start of JTFEX 99-1 stated that the exercise must be realistic:

“Featuring the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) Carrier Battle Group and the USS Kearsarge (LHD 3) Amphibious Ready Group (ARG), JTFEX 99-1 replicates emerging threats and operational challenges our military forces may encounter around the world. It is designed to meet the requirement for quality, realistic training to fully prepare our forces for joint operations when forward deployed. Participating forces will train using equipment and systems which incorporate the latest advances in technology, and which support the full range of capabilities that may be needed in various geographic areas where forces serve during their deployment.”

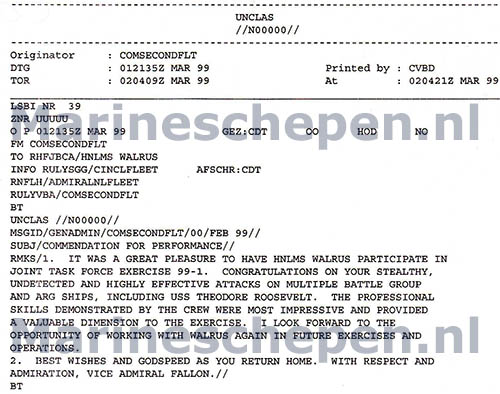

The performance of the Walrus during the exercise had also been noticed by then Vice Admiral Fallon, commander of the American Second Fleet. He wrote in the above message on March 1, 1999 to HNLMS Walrus: “It was a great pleasure to have HNLMS Walrus participate in Joint Task Force Exercise 99-1. Congratulations on your stealthy, undetected and highly effective attacks on multiple battle group and ARG [Amphibious Ready Group, JK] ships, including USS Theodore Roosevelt. The professional skills demonstrated by the crew were most impressive and provided a valuable dimension to the exercise. I look forward to the opportunity of working with Walrus again in future exercises and operations. Best wishes and godspeed as you return home. With respect and admiration, Vice Admiral Fallon” (Source: private collection J.H. Hulsker)

Everything went well

Despite the success, Hulsker remains down to earth. HNLMS Walrus had made excellent use of the conditions favoring a submarine. But, he says, “luck played a big part. It’s really hard to get that close to a carrier, because those aircraft carriers go so fast. [A diesel-electric submarine’s top speed is 20 knots but for a short time, a carrier can sail 30 kts for a long time, JK].”

“This was just one of those days when everything went well. Bad sonar conditions, a big ocean and yet we just picked them up; it was an interception that went just right. If they had changed course by 15 degrees and sailed at 30 knots, it would have been impossible for us to intercept. It’s really difficult to get into position. But we succeeded on that occasion.”

Hulsker wouldn’t have pushed it that far in a real combat situation. “I was way too close, but it was an exercise. So we went for the challenge of sneaking in through the screen undetected and then getting in front of the carrier – a classic attack. Normally we would have launched torpedoes from further away, especially if the sonar conditions were good, because those frigates would form a ring of steel around the carrier. On the high seas a submarine will be sunk if it gets too close.”

“A year later, a different Dutch submarine conducting the same exercise had no chance,” Hulsker adds.

Still, the 1999 success of HNLMS Walrus is not an isolated case. Research for the book In Deepest Secrecy revealed that Dutch submarines had more often torpedoed one (1989) or even several carriers (1983) during exercises. In 1983, three aircraft carriers (one American, one British, and one French) were ‘torpedoed’. You can find more information about this in the book.

Nine years later, the Roosevelt was hit by a simulated Italian torpedo from the Todaro, according to this photo that was taken during a similar exercise. The Todaro fired at a greater distance than the Walrus had: 8,000 yards (7.3 km). However, this was still well within range of her torpedoes. (Picture: Italian Navy)

Memory

To this day, Hulsker looks back on the exercise with satisfaction. When he meets former crew members, that 1999 exercise is always mentioned.

Was this the pinnacle of his career? No. “Of all the exercises, this was certainly one of the highlights. But after JTFEX, we did a submarine against submarine exercise near the Bahamas. Walrus against a U.S. nuclear submarine: that’s what I liked best.”

“The motivation of the crew was fantastic. If someone coughed loudly when we were in ultra quiet state, someone else would have scolded him – because you really have to be completely silent. And on that [AUTEC] range the staff could follow the torpedoes and report to us immediately whether it hit. That is incredibly motivating.”

The Walrus did not come off badly in that encounter either.

“Yes, that was a good time,” Hulsker smiles.

Sources

• Boat Walrus (2), Dutchsubmarines.com

• Deutermann, P.T., The Scorpion Hunt; De Boekerij, Amsterdam, 1996

• Interview with CDR J.H. Hulsker, Den Helder, June 2015

• Yearbook of the Royal Netherlands Navy 1999, pp. 195-196 and pp. 229-230

• Margés, J.M., Klaver troef in Amerikaans eindexamen; Alle Hens, April 1999

• NAVY WIRE SERVICE, USS Theodore Roosevelt CVBG, USS Kearsarge ARG to conduct Joint Task Force Exercise; Fas.org, originally communicated January 21, 1999

• Panhuis, B., Nederlandse marine kijkt jaloers naar Amerikanen, Trouw, March 11, 1999

• Ship’s log HNLMS Walrus, May 7, 1998 – March 2, 1999; Semi-static Information Management, Ministry of Defense-DMO-JIVC-Information Management

• Ship’s log HNLMS Walrus, March 2, 1999 – June 3, 1999; Semi-static Information Management, Ministry of Defense-DMO-JIVC-Information Management

• Woodward, S.; One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander; Naval Institute Press, 1997